California Dreaming? Offshore Wind on the West Coast

June 3, 2020

Offshore wind energy development is in its infancy in the United States compared to Europe. The nation’s first operational project came online in 2016 off the coast of Rhode Island. A few other projects have since gained traction up and down the Eastern seaboard. Deep, crowded waters and technological barriers have largely kept the West Coast out of the discussion. But, as floating turbine technologies become commercially feasible and open up the potential for massive amounts of wind power in California waters, recent inter-agency cooperative efforts have begun to clear a path, and developers are lining up.

Offshore wind energy development is in its infancy in the United States compared to Europe. The nation’s first operational project came online in 2016 off the coast of Rhode Island. A few other projects have since gained traction up and down the Eastern seaboard. Deep, crowded waters and technological barriers have largely kept the West Coast out of the discussion. But, as floating turbine technologies become commercially feasible and open up the potential for massive amounts of wind power in California waters, recent inter-agency cooperative efforts have begun to clear a path, and developers are lining up.

This article surveys the current regulatory status of offshore wind development in California and the primary federal and state permitting processes to which it will be subject.

Status of Offshore Wind in California

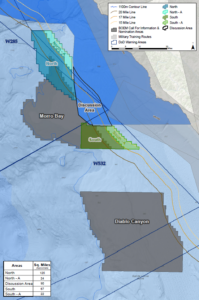

The United States Bureau of Ocean Energy Management (BOEM) oversees the leasing and development of renewable energy projects on the outer continental shelf. In October 2018, BOEM published a Call for Information and Nominations identifying three call areas off the California coast that may be suitable for wind development: Morro Bay and Diablo Canyon in central California, and Humboldt in northern California. Fourteen companies responded to the call expressing interest in developing offshore wind facilities in those areas.

BOEM originally expected to begin issuing leases in 2020. However, in August 2017 the Department of Defense (DoD) issued a Mission Compatibility Assessment concluding that wind development in Morro Bay and Diablo Canyon would conflict with military operations. Because BOEM cannot issue leases without DoD approval, DoD’s position effectively froze the process for the two central coast call areas.

Recently, however, lawmakers, BOEM, DoD, and other federal agencies have arrived on a tentative deal by which parts of the Morro Bay call area that were previously ruled incompatible for wind farms by DoD would be opened for development, in exchange for a legislative moratorium on turbines within nearby areas identified as critical for DoD operations.

Following the meetings, the California Energy Commission (CEC) released a tentative map of offshore wind development areas on 7 February 2020 which depicts parts of the original Morro Bay call area as open to development and also contains a “discussion area” in nearby waters. The CEC is soliciting public comments on the tentative map, which are due 31 July 2020. The depicted development areas have not been officially vetted by federal or state agencies, and part of the discussion area overlaps with a National Marine Sanctuary where BOEM is prohibited from granting leases. Nevertheless, the CEC map and tentative deal with DoD indicate a potential path forward for offshore leasing to begin in California.

Regulatory Considerations for California Offshore Wind

With federal leasing in sight, hopeful offshore wind developers in California will need to consider how the state’s various regulatory requirements will interact with the federal process. The region’s jurisdictional web is complex: one study estimated that offshore wind projects in California may require up to 28 separate approvals from federal, state, and local authorities.

After summarizing the federal offshore leasing process, which applies to any project on the outer continental shelf, we highlight certain California regulations that are likely to apply to wind projects sited off the California coast.

Federal Offshore Leasing Process

The Energy Policy Act of 2005 granted BOEM the authority to oversee the leasing and development of renewable energy projects on the outer continental shelf. See 43 U.S.C. § 1301 et seq.; 30 C.F.R. § 585.100 et seq. The agency must issue leases for offshore projects on a competitive basis following several stages of public engagement.

Under the agency’s regulations, a private developer may submit an unsolicited proposal to lease any area within federal waters for a wind energy facility. 30 C.F.R. § 585.230. In response to a bid or by its own volition, BOEM may issue a Request for Interest to solicit public comment regarding development in the area and to determine whether there is a competitive leasing interest. 30 C.F.R. § 585.231. If BOEM finds a competitive interest, it will issue a Call for Information and Nominations to collect development plans from interested companies and gather public input on site conditions, resources, and existing uses of the potential lease area.

If BOEM decides to issue a lease, it will hold a competitive auction (after a limited National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) environmental review, described below) and grant the winner the exclusive right to conduct site assessment activities pursuant to a Site Assessment Plan (SAP) that must be prepared within one year of granting the lease, subject to extension. 30 C.F.R. § 585.605. If BOEM approves the SAP – often with conditions – the developer has five additional years to assess environmental conditions at the site and propose a Construction and Operations Plan (COP) that includes a detailed project description and proposals for minimizing environmental impacts. 30 C.F.R. §§ 585.235(a)(2); 585.601(b); 585.626(b). BOEM may then conduct a complete environmental analysis under NEPA and subsequently approve, deny, or conditionally approve the developer’s COP. 30 C.F.R. § 585.628(b).

Experience on the East Coast suggests that the BOEM leasing process takes years to complete. For example, it took five-and-a-half years from the time BOEM issued a Call for Information and Nominations for the Virginia Wind Energy Area to hold a competitive auction and approve the winner’s SAP. Similarly, for a call area offshore of Rhode Island and Massachusetts, over six years elapsed between issuing a Call and approving the winner’s SAP. Neither lessee has submitted a COP, and the multi-year, comprehensive environmental review under NEPA has yet to begin for either project.

Other Federal Regulatory Considerations

A number of federal agencies are involved in the permitting process for any offshore wind energy project. We discuss several below. Note that the President’s One Federal Decision Policy established in Executive Order 13807 calls for agency coordination such that federal environmental review is to be completed within two years to the extent possible.

BOEM. BOEM serves as lead agency under NEPA for offshore wind projects. The environmental impact review process under NEPA is typically twofold as applied to offshore wind. At the leasing and SAP stage, BOEM will usually prepare an Environmental Assessment (EA) limited to considering the environmental impacts of the anticipated site characterization activities (e.g., installation of meteorological towers) rather than the anticipated impacts of the project as a whole. Then, once site assessment is complete and the developer submits a COP, BOEM will conduct a more thorough NEPA analysis of project-wide impacts before approving or denying the COP. The size and nature of offshore wind projects almost certainly call for an Environmental Impact Statement (EIS) rather than a more limited EA at the COP stage, which has been true for most East Coast projects.

The U.S. District Court for the District of Columbia has twice rejected claims that offshore wind development should be conducted pursuant to a single, comprehensive NEPA review, rather than bifurcated between the SAP and COP. Fisheries Survival Fund v. Bernhard, No. 16-cv-2409 (TSC), 2020 WL 759099 (D.D.C. Feb. 14 2020); Fisheries Survival Fund v. Jewell, 236 F. Supp. 3d 332 (D.D.C. 2017).

National Marine Fisheries Service / U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. The BOEM leasing and development process triggers consultation with the National Marine Fisheries Service (NMFS) and/or the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS) under Section 7 of the Endangered Species Act (ESA). If the project may adversely affect a listed species, BOEM must formally consult with NMFS (for aquatic species) or USFWS (for terrestrial species) and seek a biological opinion. The agencies may issue an Incidental Take Statement (ITS) along with a biological opinion if they find the incidental take of a listed species is foreseeable and not likely to jeopardize the continued existence of a listed species and/or result in the destruction or adverse modification of critical habitat. This process generally occurs concurrent with (although separate from) a project’s NEPA review.

Many East Coast projects have engaged in ESA Section 7 consultation. For example, developers of the Vineyard Wind Offshore Wind Facility (Vineyard Wind) near Massachusetts requested ESA consultation with MNFS in December 2018, and a biological opinion is expected in September 2020.

U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. The Clean Water Act (CWA) regulates activities that affect waters of the United States (WOTUS), including coastal waters. Offshore energy projects that create point source discharges of waste, either during construction or operation, would require a National Pollutant Discharge Elimination System (NPDES) permit from the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). The issuance of a NPDES permit would likely require a Section 401 water quality certification from EPA, which could be processed concurrently.

Additionally, offshore wind projects located 25 nautical miles or more from the state seaward boundary are subject to federal air quality standards and will likely require an air permit from EPA certifying compliance with the Clean Air Act (CAA). The Vineyard Wind permitting timeline anticipates an EPA air permit within three years of applying.

U.S. Army Corps of Engineers. The construction phase of any offshore wind project will likely also require a CWA Section 404 permit from the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers (Army Corps) for dredged or fill material discharged into WOTUS. The Vineyard Wind permitting timeline anticipates CWA approvals from both the Army Corps and EPA within three years of applying. While wind projects off the California coast likely will use floating turbine technologies that are less intrusive than driving wind turbine towers directly into the seafloor (as is often possible in shallower East Coast waters), they will likely still trigger the need for a 404 permit.

Section 10 of the Rivers and Harbors Act additionally requires authorization from the Army Corps for the construction of any structure in, over, or affecting any navigable water of the United States. East Coast projects such as the Bay State Wind offshore wind farm have sought such permits, and any wind project off the coast of California will likely require the same.

State Regulatory Considerations

Federal permitting requirements aside, there are a variety of state-specific regulations that will apply to offshore wind projects in California. We lay out several participating state agencies below. State-level reviews should be coordinated with the CEQA process led by the State Lands Commission. A 2016 Memorandum of Understanding between the U.S. Department of the Interior (the parent agency of BOEM) and the state of California, and the Intergovernmental Renewable Energy Task Force created the same year, should further coordinate the federal and state permitting processes for offshore wind farms.

California State Lands Commission – CEQA. CEQA is a state-law NEPA analogue that requires most large development projects in the state to undergo environmental review before receiving discretionary approvals. CEQA requires the California State Lands Commission (SLC), as the presumptive lead agency in this context, to analyze the environmental impacts of its leasing decisions (described below). Other state and local agencies from whom discretionary approvals are required – for example, the California Coastal Commission (CCC), California Department of Fish and Wildlife (CDFW), and the county or city through which the project interconnects – would provide additional input as responsible agencies.

The CEQA process would take at least one year, if not longer, to complete, but should run concurrently with BOEM’s NEPA review of a project’s COP. CEQA and NEPA reviews for an offshore project would likely be combined into a single document because CEQA encourages combined CEQA/NEPA reviews where possible. Combining the state and federal environmental reviews would also allow the SLC to participate in the process as a co-lead agency while allowing BOEM to take a de facto lead role.

California State Lands Commission – Lease. The SLC has jurisdiction over 4 million acres of sovereign tidal and submerged lands across the state, including most submerged lands adjacent to the coast. An offshore wind project’s interconnection facilities would almost certainly pass through state waters and require a lease from the SLC (unless they passed through legislatively granted lands instead).

The SLC determines whether to grant a lease based on a number of factors, including consistency with the public trust under which the SLC manages state land and waters; protection of natural resources; preservation or enhancement of the public’s access to state lands; the size, location, intended use, and described need for the project; the project’s relationship to the surrounding environment; and whether the size of the project is appropriate for the location and type of use proposed. Although the SLC has never before considered a lease application for an offshore wind project’s gen-tie through coastal waters, developers of properly-sited and mitigated projects would have a compelling argument that their applications are consistent with the public interest given California’s ambitious requirement that 100 percent of the state’s electrical sources be carbon-free by 2045.

California Coastal Commission. The CCC has jurisdiction over the coastal zone extending approximately 1,000 feet inland and three miles offshore. See United States v. California, 135 S. Ct. 563 (2014). The CCC has two independent jurisdictional grounds over offshore wind projects described below. These processes may be addressed concurrently but timing may depend on other agency approvals.

The federal Coastal Zone Management Act (CZMA) provides that any federal agency activity—such as a BOEM lease sale—that affects the coastal zone “shall be carried out in a manner which is consistent to the maximum extent practicable with the enforceable policies” of the California Coastal Program, 16 U.S.C. § 1456(c)(1), which include public access, recreation, the marine environment, land resources, and other issues. See Cal. Pub. Res. Code § 30200 et seq. In California, the CCC is typically responsible for making such determinations unless delegated to a local agency via a certified Local Coastal Program. Federal licenses or permits affecting the coastal zone cannot be issued until the CCC certifies that the proposed activity complies with enforceable state policies (although the Secretary of Commerce may override a state objection). 16 U.S.C. § 1456(c)(3).

The CCC also has jurisdiction through the California Coastal Act, which separately requires a coastal development permit from the CCC for projects proposed within the coastal zone. Cal. Pub. Res. Code § 30600. When determining whether to issue coastal development permits, the CCC looks to the same California Coastal Act policies it considers when issuing consistency determinations or certifications under the CZMA. Cal. Pub. Res. Code § 30604.

California Department of Fish and Wildlife. Offshore wind developers in California must also contend with the California Endangered Species Act (CESA), Cal. Fish and Game Code 2050 et seq., to the extent their projects directly or indirectly affect species protected under the state statute. Unlike the Federal ESA, CESA requires all impacts to be fully mitigated but, on the other hand, has a narrower definition of incidental take than the Federal ESA.

CDFW usually processes incidental take permits in about six months, concurrent with the CEQA process. In the alternative, CDFW may issue a 30-day consistency determination (CD) if the developer obtains federal incidental take authorization under the Federal ESA that is consistent with California requirements for a particular species. Whether a CD would be an option for an offshore wind project would depend on the species involved as well as the preference of the CDFW staff assigned to the project.

Other Federal and State Permitting Considerations

Aside from the primary state permitting considerations above, there are a host of other, more resource-specific federal- and state-level approvals that may be required for offshore wind projects in California. For example, offshore wind permitting may require the lead agency to consult with the California State Historic Preservation Officer (SHPO) pursuant to Section 106 of the National Historic Preservation Act and a 2019 Programmatic Agreement between BOEM, SHPO, and the Advisory Council on Historic Preservation if the project would affect properties listed in the National Register of Historic Places or properties eligible for listing. The Marine Mammal Protection Act requires an incidental take authorization from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration if marine mammals are to be affected by the project. The United States Coast Guard may require a Private Aids to Navigation permit to ensure turbines are properly marked. Additionally, projects that affect rivers, streams, or lakes in California may need to obtain a Lake and Streambed Alteration Agreement from CDFW.

Developers must also consider county- and city-level zoning requirements for onshore support infrastructure. And, as is common with most onshore infrastructure projects, the agencies processing a project application will need to consult with Native American tribes to determine whether the project will impact tribal fishing rights, sensitive archaeological resources, or tribal use of marine waters. While these other permitting considerations are numerous, they are generally secondary to the primary permitting mechanisms discussed above and would be processed concurrently with a project’s NEPA/CEQA environmental impact review.

Conclusion

California offshore wind development is in the offing. Wind developers with long-term plans for the West Coast should start mapping out their entitlement and agency engagement strategies soon, given the length and complexity of the permitting processes involved.